Stories of Hope: Myra

Published on: June 04, 2020

“A year ago, I was thrilled to survive…and looked forward to what the future would bring. I would have never imagined a year from that day I would be getting ready to go to work in the midst of a pandemic,” Myra wrote on her blog nearly one year after the cranioplasty that would signify the beginning of the next chapter of her recovery.

“A year ago, I was thrilled to survive…and looked forward to what the future would bring. I would have never imagined a year from that day I would be getting ready to go to work in the midst of a pandemic,” Myra wrote on her blog nearly one year after the cranioplasty that would signify the beginning of the next chapter of her recovery.

Myra, a 27-year-old nurse practitioner, is one of the many healthcare workers now deemed essential during the COVID-19 pandemic. She also holds a designation that few her age have —she’s a survivor from a severe stroke that almost took her life.

A Christmas Nightmare

It was December 24, 2018, the night of her annual family Christmas Eve party, and Myra was slowly recovering from a week-long sore throat. This year, the holidays promised to be special — Myra had just recently started her first job as a newly-minted nurse practitioner, she had a new apartment, and she was recently engaged. She was looking forward to celebrating all of these big events in her life with family. But a severe, unrelenting headache caused her to leave the party early. This was a headache that she would later call the worst headache of her life, and one that stubbornly lingered despite all kinds of migraine cocktails and opiate pain medications.

Despite some protestation on her part, her family brought her to a local hospital, where some relief set in after the emergency room physician expressed equal concern at the severity of her headache, which had only gotten worse since it began. While an initial CT scan of her head was normal, a painful lumbar puncture suggested that she had elevated intracranial pressure, and a plan to transfer her to Boston to receive more specialized care was set in motion. These would be her last clear memories for over a week, as she was quickly taken to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

“No matter how hard I rack my brain for memories after that ambulance ride, they just do not exist anymore,” she recalls. “The only thing I remember is darkness and terror.”

Myra was found to have a cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, or a clot in one of the veins around her brain. Her clot happened to extend from her right transverse sinus into the internal jugular vein — the last stop for blood to make its way out of the right side of her brain and a particularly bad place to have an obstruction. While this large clot was the cause of her severe headaches, her initial CT scan showed that she had been spared from suffering a stroke or hemorrhage. However, the clot would likely keep getting bigger and more dangerous without treatment, so she was started on a continuous infusion of heparin, a strong blood-thinning medication.

A Dreaded Complication

A Dreaded Complication

Only hours later, after settling in the neurology step down unit, Myra became suddenly unresponsive. She was quickly examined by her team, who found that her right pupil was dilated and no longer reacting to light, and her body was making abnormal reflexive movements called decerebrate posturing in response to any kind of stimulation. All of these were signs that pointed toward impending brain herniation — a life-threatening shifting of brain structures due to severe compression.

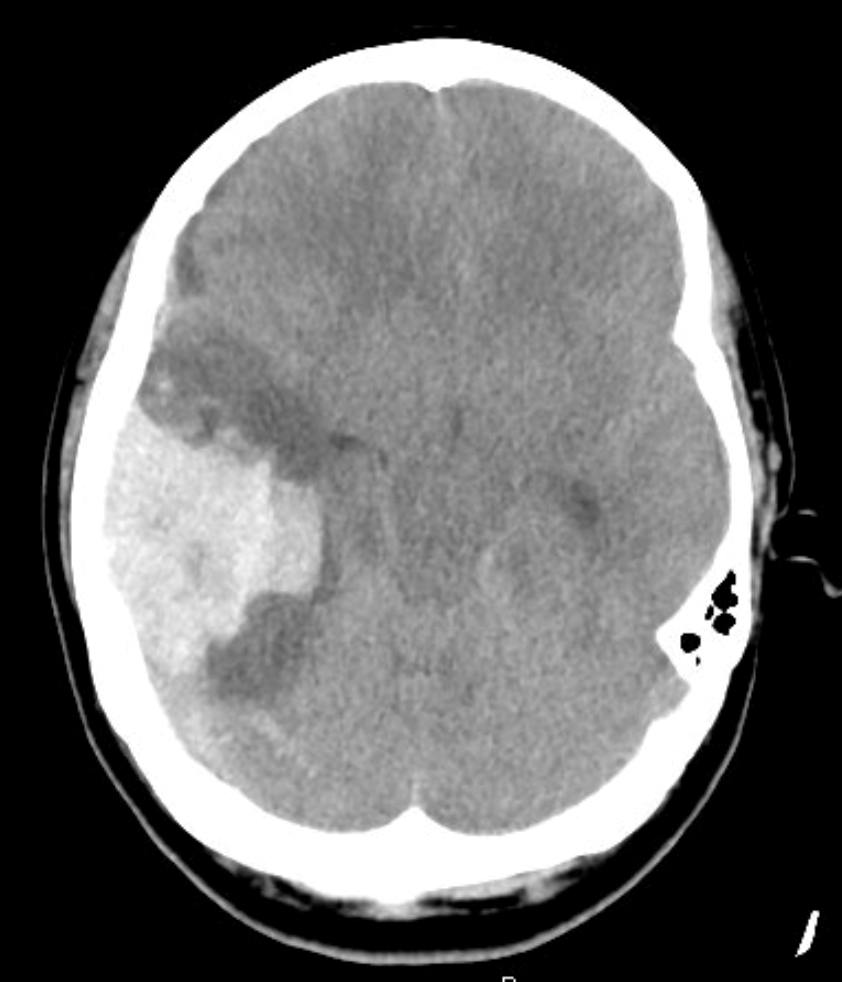

Her team of doctors and providers acted quickly. She was intubated and put on a ventilator, given a dose of 23.4% saline (a concentrated salt solution to reduce the swelling in her brain), and her heparin infusion was stopped and reversed with an antidote presuming that she had had a bleeding event. She was then rushed to the CT scanner en route to the operating room for emergency neurosurgery. Imaging confirmed what had been feared and suspected: Myra had suffered a massive hemorrhage into her brain tissue that would require emergency decompressive surgery.

Myra has limited memory of her first week following surgery in the neuroscience ICU. Although her brain was the immediate concern, the rest of her body was part of the fight, too. Her ICU team would face several battles in the coming week. Her platelets, a special type of blood cell, and other blood proteins that help form blood clots, were found to be dangerously low due to an inflammatory response called disseminated intravascular coagulation that put her at risk for more bleeding. She also started having fevers from a severe pneumonia. Despite having just had a large hemorrhagic stroke, the ICU team had a difficult decision to make — when to restart her blood-thinning medication. Athough her brain was healing, the large clot that caused her headaches was still present and not being treated. With the help of antibiotics and blood transfusions, Myra’s infection and her low blood counts improved. The team eventually restarted her blood thinner after a repeat CT scan showed no new bleeding. At first, Myra would only wake up for brief periods of time and wasn’t able to communicate. Soon, even this had improved: She was moving her arms and legs and giving the ever-optimistic thumbs up to the ICU team during daily exams. Everything finally seemed to be going in the right direction for Myra; it was almost time to remove the breathing tube.

She recalls her first concrete memory being a sea of unfamiliar faces gathered around her while she had her breathing tube taken out. She describes an incredible sense of frustration in being unable to articulate her own thoughts.

She recalls her first concrete memory being a sea of unfamiliar faces gathered around her while she had her breathing tube taken out. She describes an incredible sense of frustration in being unable to articulate her own thoughts.

“I remember having rational thoughts…but it wouldn’t come out of my mouth that way…it’s like someone cut the brakes [to] your car.”

At times she recalls seeing faces, colors, and at one point an array of glowing fiber optic cables that she would later learn weren’t actually there. For a woman who had always been a self-proclaimed “science nerd,” this was difficult to comprehend.

“I had no idea what was reality and if what was happening was real or still a nightmare.”

She experienced periods of anger and lability during this time, and it took seeing her scars in a mirror before she was able to grasp the extent of her injury.

Throughout everything that had happened, Myra’s family was a point of constant comfort for her. They fueled her motivation to regain some sense of normalcy, though that would prove to be a moving target. She made great strides even while she was in the hospital and left for acute inpatient rehabilitation 17 days after she first arrived in the emergency room, with only mild deficits in her arm strength and vision. Her stay at rehab was similarly brief, and she even graduated from home physical therapy just a week after leaving inpatient rehab. Her rehabilitation success was not without consequence, however.

“I tried to rush things as much as possible. Pushing myself too much, increasing my anxiety. You’ve got to give yourself a break, sometimes the body can’t move as fast as you want it to.”

Recovery: It’s Not Just Physical

By all accounts, Myra has had a miraculous recovery. Her physical deficits are almost non-existent, and she has truly beaten all odds and expectations.

“She literally told me, ‘I thought you were dead on the table,’” Myra says, recounting a discussion with her neurosurgeon. “[But] I can walk, talk, drive…what’s been lasting has been the psychological aspects.”

For Myra, like many other stroke survivors, there have been significant and unexpected psychiatric hurdles. These hurdles are the enduring aftershocks of her brain injury, and the trauma inflicted by critical illness and the ICU environment. There were periods of time when she felt so anxious and depressed that she couldn’t even leave her house. She recalls being surprised in conversations with her neurologist, when she was told that anxiety was an expected complication.

“I don’t think it was ever brought up…I remember saying, ‘If it was going to happen, why didn’t [we] treat earlier.’”

Myra’s initial instinct was to intellectualize her experience by researching her diagnoses and her surgeries, but this quickly led to more nightmares. Instead, she found counseling to be immensely helpful in restructuring some of her coping mechanisms and allowing her to heal from her trauma. Even after her cranioplasty, one of the last physical hurdles of her recovery, life had not returned to the same “normal.”

Myra’s initial instinct was to intellectualize her experience by researching her diagnoses and her surgeries, but this quickly led to more nightmares. Instead, she found counseling to be immensely helpful in restructuring some of her coping mechanisms and allowing her to heal from her trauma. Even after her cranioplasty, one of the last physical hurdles of her recovery, life had not returned to the same “normal.”

“It had changed me, both physically and psychologically…my perspective on things had changed permanently,” she recalls, endorsing a newfound self-confidence that simply was not part of who she was prior to her stroke. She felt rejuvenated as an individual and as a practitioner. “I now realized that life was too short to push aside your own happiness.”

From Patient to Practitioner in the Time of a Pandemic

“Why did I survive?” Myra asks. “It was a lot of luck. The luck of having encountered a special group of doctors at each critical moment…I’ll pay it forward as much as I can.”

A year after her initial injury, Myra returned to work as a nurse practitioner. Despite her background, Myra frequently found medicine to be reductive as a patient.

“I felt like I was being treated like a series of scans on a screen,” she recalls of the months long waiting time before her cranioplasty, which she suggested moving up. “I told them my concerns…even though the logical part of my brain knew it would be stupid.”

When reflecting on ways that her experience changed her clinical practice, she notes that she is very mindful of the language she uses, paying special attention to the verbal and nonverbal manner she communicates with patients.

“Words have meaning, experience matters,” she reflects. Myra was more ready than ever to fulfill the role of advocate for so many of her patients after having been one herself.

Being an essential medical provider during this current health crisis, after so recently being a patient herself, has brought on some new hurdles.

“Especially now, with COVID-19 and intubation being constantly talked about daily…there is a lot of psychological trauma that comes along with an ICU experience,” Myra explains. She counts herself as one of the lucky ones, however. Reflecting on her experience in comparison to that of current ICU patients, “It was awful going through it then, but I can’t imagine how it must be now. I woke up to chaos, but I had some familiarity in the chaos.”

At the current moment, critical care capacity at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, like many other hospitals across the world, is at an unprecedented high. The neurology step down unit, PACU, and multiple medical and surgical wards have been converted into ICUs to accommodate the surge of COVID-19 patients. There are no families or visitors allowed in the hospital. All patient-facing healthcare workers are wearing masks, goggles and sometimes shields that obscure their faces. In this time, when families cannot see their loved ones, and patients are critically ill on a scale that many of us have never seen before, Myra’s reflections are a poignant reminder to us all.

“Going through everything from start to finish, the words are what I remember most. Little things that we say in the chaos of everything, a little word here or there, hope or something that we think is nothing, it could even be our tone of voice…it all matters.”