Emergency Neurological Life Support: Understanding Its Applicability and Limitations in Africa

Published on: October 20, 2023

Morgan Prust MD1, Susan Yeager DNP2,3, Halima Salisu Kabara CCRN4, Ismail Hassan MBBS5, Misbahu Ahmad MBBS5, Mustafa Miko Abdullahi MBBS6, Becca Stickney3, Sarah Wahlster MD7, Sarah Livesay DNP3,9, Yasser B. Abulhasan MBChB3,9

Introduction

|

Geographical representation of participants across Africa

|

The Emergency Neurological Life Support (ENLS) certification course sponsored by the Neurocritical Care Society provides standardized approaches to the acute management of commonly encountered neurologic emergencies. Initially published in 2012, ENLS is currently in its fifth version, and reflects the most up-to-date standards of emergency neurologic care.1 Instruction in ENLS is commonly delivered over a short course spanning 1-2 days and is applicable to any healthcare worker participating in the early chain of survival and recovery for common neurologic emergencies. The course covers 14 modules including intracranial hypertension, traumatic brain injury, ischemic stroke, and approach to coma, to name a few.

The management algorithms embedded in ENLS have been developed and fine-tuned over the past decade by experts predominantly in high-income countries (HICs) practicing in well-resourced healthcare environments. These algorithms, therefore, are predicated on timely access to a variety of diagnostic and therapeutic resources to guide acute decision-making and intervention. They may have more limited applicability in resource-limited settings where key resources are absent or unavailable within an ideal time frame for patients with an acute neurologic injury.

There is growing interest in the applicability of ENLS in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the burden of acute neurologic illness is high and the availability of neurologic or critical care expertise is severely constrained.2–4 Because ENLS can be delivered asynchronously via remote access to online course modules, it represents as a feasible and effective means of disseminating neurocritical care knowledge to healthcare workers in remote regions with a low density of neurologic or critical care expertise, and may help strengthen the early chain of survival for patients in those settings. Cohort studies of LMIC healthcare workers undergoing ENLS trainings have been published from Nepal,5 Cambodia,6 and Sub-Saharan Africa.7 These studies have demonstrated widespread enthusiasm for ENLS and recognition of the need to advance neurocritical care training in LMICs. Participants across each of these studies demonstrated increases in knowledge and subjective comfort managing neurologic emergencies, but expressed concerns about ENLS’s limited applicability to their local healthcare contexts, where access to resources taken for granted in most HIC hospital settings is severely limited or absent.

The current standard of care for patients with acute neurologic injuries is highly resource intensive. Also, neurological emergencies are often time sensitive. As practiced in HICs, standard neurocritical care practices rely on immediate access to a variety of high-tech, high-cost diagnostic and treatment modalities delivered in dedicated neurosciences ICUs by large teams of highly specialized practitioners who are available for bedside and operative care at all hours of day or night. By contrast, care delivery in most of Sub-Saharan Africa healthcare settings is limited by resource gaps across the continuum of care, including prehospital care systems, ICU beds, neurology and neurosurgery expertise and availability, nursing staff, neuroimaging, essential medications, and neurorehabilitation.4 Moreover, even if services are available, widespread pay-in-advance fee-for-service models place them out of reach for patients and families unable to finance the cost of care.

Recognizing the potential of ENLS to enhance neurocritical care knowledge and support the delivery of life saving care for patients in resource-limited settings, yet wishing to better understand its current limitations in LMIC contexts, we formed the ENLS Africa Task Force in 2022. Our goal was to investigate the implementation challenges of ENLS in Africa, with the ultimate aim of proposing rational, data-driven adaptations to ENLS that may enhance its utility in Africa and other LMIC settings.

Partnership with Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital in Kano, Nigeria

|

(Left to right) Dr. Ismail Hassan (AKTH Neurosurgery), Dr. Susan Yeager (The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center), Halima Salisu-Kabara (AKTH critical care nurse), and Dr. Morgan Prust (Yale School of Medicine)

|

Leveraging pre-existing partnerships between NCS and colleagues at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH) in Kano, Nigeria’s second largest city, we developed a plan to host a 2-day live training event for healthcare workers from across the African continent. In order to maximize representation from as many nations and levels of resource availability as possible, we designed a hybrid event that would allow 100 participants to join in person at AKTH, and 100 to join remotely. We recruited our participants through an extensive word-of-mouth campaign among networks of contacts and professional organizations in Africa. We designed surveys to capture data regarding the neurocritical care capacity and level of resource availability specific to each ENLS module for participants to complete throughout the course. These surveys were designed to assess participants’ access to neurocritical care resources at their local institution (number of ICU beds, availability of neurologists and neurosurgeons, availability of general emergency medicine and critical care resources, and availability of key neurocritical diagnostic and treatment resources), and for each ENLS module, queried the specific resource gaps that limit the management algorithm’s utility in their practice settings, and asked open-ended questions regarding existing protocols and barriers to delivering care for individual ENLS diagnoses.

After several months of planning, participant recruitment, and coordination among our task force, we hosted the event on July 10 and 11, 2023. Dr. Morgan Prust MD, a neurointensivist at Yale School of Medicine focused on global health and neurocritical care, and Dr. Susan Yeager DNP, a neurocritical care doctor of nursing practice at The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center and current NCS treasurer, both traveled from the US to Kano to direct the course in person. Dr. Ismail Hassan, director of neurosurgery at AKTH, Dr. Mutapha Miko Abdullahi, director of anesthesia at AKTH, and Halima Salisu-Kabara, senior nursing educator and retired critical care RN, worked to coordinate the recruitment and logistics for the in-person event in Kano. In parallel, NCS hosted an online platform for participants joining remotely, which was coordinated by NCS operations specialist Becca Stickney, with multiple ENLS trainers joining live to answer participants’ questions. Our participants represented 20 African nations and included physicians from multiple specialties, nurses, and physiotherapists.

Despite occasional power failures to the packed lecture hall in Kano, the in-person and virtual courses ran smoothly and generated tremendous energy from participants. After each ENLS module, participants completed their neurocritical care capacity surveys and asked questions, often focused on how to approach challenging clinical scenarios without key resources. Course participants demonstrated a keen desire not only to master the content of the ENLS course but also to engage with the challenge of designing treatment algorithms that may be more reflective of the resource gaps that exist in many LMIC hospital settings. Through our conversations over the two-day event, we heard about many of the resource constraints that limit acute care delivery, and the creative solutions to work around them. For example, if power outages affect the lighting in the neurosurgical operating theater at AKTH, OR staff will illuminate the surgical field with flashlights from their phones.

|

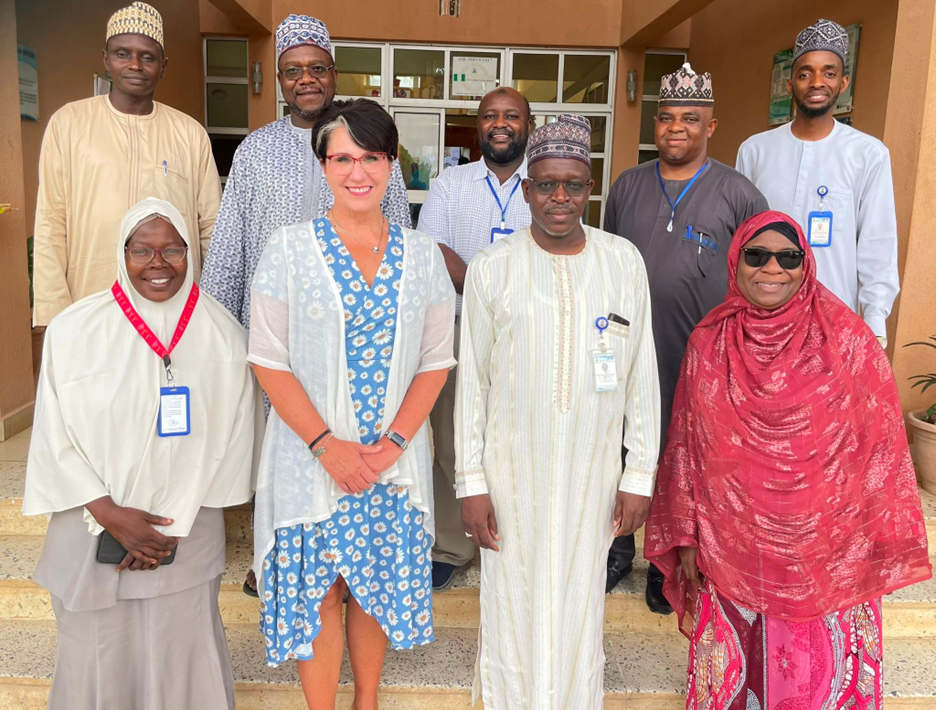

Dr. Yeager poses with the chief medical officer (front center) and chief nursing officer (front left) and other senior hospital staff at AKTH

|

During their visit to Kano, Dr. Prust and Dr. Yeager experienced the irreplaceable value of face-to-face encounters in forming new connections. They discussed the course with the chief medical officer and chief nursing officer of AKTH. Discussions are underway to integrate ENLS into the standard platform of trainings within the hospital Life Support Center for physician and nursing education. We are also partnering with hospital leadership at AKTH to establish a Nigerian NCS chapter. From our sample of participants, we have recruited a working group of physicians, nurses, and physiotherapists from Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Uganda, Zambia, and Senegal, who will partner with our task force to analyze the survey data generated from the course and develop a curriculum for emergency neurologic care in resource-limited settings. This process is just getting started and we look forward to reporting on the results of our work over the next several months.

Next, the Pediatric Neurocritical Care Education Series is a bi-monthly webinar developed by members of the Pediatric Neurocritical Care Research Group (PNCRG) Subcommittee on Education.12 This live lecture series utilizes a freely accessible video platform that has been attended by 102 participants from African countries (Fig 3). The series includes four types of sessions: topical lecture, case-based panel discussion, skills lab, and journal club. The content of each session is tailored to the level of a pediatric neurocritical care trainee and is relevant to various disciplines. Topics covered to date include post-cardiac arrest care, traumatic brain injury, central nervous system infections, continuous electroencephalogram monitoring, and neurocritical care in low and middle-income countries. All sessions are recorded and posted to an online video platform for subsequent viewing. These initiatives offer excellent inclusive learning and networking opportunities for clinicians in low-resource regions (Fig 3).

Despite the sessions being free and accessible to anyone, the group has encountered several challenges. For example, there may be a segment of the population that remains unaware of these sessions despite utilizing social media and an email distribution list. Additionally, there may be language barrier-related issues, as all sessions are conducted in English without any captions or other forms of translation, posing a challenge for individuals who may not be proficient in English. Finally, some individuals may not have sufficient internet access or bandwidth to stream the sessions effectively.

To address these challenges, the group is actively exploring potential solutions to increase awareness, such as expanding its reach via different social media channels and professional society email distribution lists. Additionally, efforts are underway to provide language support tools such as captions or translations to make the sessions more inclusive. Finally, alternative means of content delivery are being explored to ensure accessibility for individuals with limited internet access or bandwidth.

Finally, it is crucial to acknowledge the remarkable and sustained efforts of various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and academic institutions dedicated to education and sustainability in low-resource settings. These entities play a significant role in providing practical on-the-job training, often in challenging conditions, with the aim of improving access to essential critical care services. Examples of such organizations include Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the Alliance for International Medical Action (ALIMA), and various hospital partnerships. Programs such as Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT)13 are specifically designed to stabilize the ABCs (Airway, Breathing, Circulation) and provide essential care for neurological emergencies, setting the stage for more advanced curriculums. In addition, important neurological educational initiatives have been undertaken by the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) and the Foundation for International Education in Neurological Surgery (FIENS).14-16

Translating Data Into Action

|

Dr. Prust and Dr. Yeager listen to a course participant discussing challenges in managing patients with traumatic brain injury in Nigeria

|

Given the enormous unmet burden of acute neurologic disease in LMICs, building a global workforce of providers skilled in the acute diagnosis, stabilization, and management of acute brain injury must be a leading priority of the worldwide neurocritical care community. Short courses like ENLS cannot replace longitudinal training opportunities for workforce development in LMICs, nor can they close gaps in essential material resources like CT scanners or essential medicines. ENLS does, however, provide a platform to deliver standardized training on key neurocritical care topics to a wide spectrum of providers. We strongly believe that understanding the limitations of ENLS in resource-limited environments can provide the basis for evidence-based guidelines that organize treatment around optimal use of available resources. We are hopeful that equipping front-line providers in LMICs with decision support tools that reflect the realities they face on the ground will improve standards of care for patients with acute neurologic illness worldwide.

Beyond the contents of the ENLS course, we are also hopeful that our engagement with leaders in neurology, neurosurgery, and critical care from across Africa will provide further opportunities for capacity-building, and that the momentum and connection generated during this event may catalyze further conversations at local, national, and regional levels on how to advance care for the enormous and growing population of patients with acute brain injury worldwide. Moreover, we know that the resource constraints commonly encountered throughout Africa also affect healthcare workers and patients in LMICs across the globe. We welcome any engagement with clinicians, researchers, policymakers, or other stakeholders seeking to make a difference in advancing global neurocritical care.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the following faculty members who recorded lectures for the ENLS Africa course: Yasser B. Abulhasan, Mary Kay Bader, Jamil Dibu, Salia Farrokh, Jennifer Frontera, Sarah Livesay, Casey May, Morgan Prust, Sarah Wahlster, Katja Wartenberg, and Susan Yeager. We also wish to thank the following faculty members for joining remotely to answer online participants’ questions: Raffaele Aspide, Sylvia Bele, Walter Mickey, Remi Okwechime, Shaheen Shaikh, and Sarah Wahlster.

References

1. Smith, W. S. & Weingart, S. Emergency Neurological Life Support (ENLS): what to do in the first hour of a neurological emergency. Neurocrit Care 17 Suppl 1, (2012).

2. Feigin, V. L. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 18, 459–480 (2019).

3. WHO. WHO | ATLAS Country Resources for Neurological Disorders. WHO (2017).

4. Prust, M. et al. Providing Neurocritical Care in Resource-Limited Settings: Challenges and Opportunities. Neurocrit Care 37, 583–592 (2022).

5. McCredie, V. A. et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of the Emergency Neurological Life Support educational framework in low-income countries. Int Health 10, 116–124 (2018).

6. Barkley, A. S. et al. Teaching the Emergency Neurologic Life Support Course at Two Major Hospitals in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. World Neurosurg 141, e686–e690 (2020).

7. Tiamiyu, K., Suarez, J. I., Komolafe, M. A., Kwasa, J. K. & Saylor, D. Effectiveness, relevance, and feasibility of an online neurocritical care course for African healthcare workers. J Neurol Sci 431, (2021).

Author Affiliations

1Yale School of Medicine, Department of Neurology, New Haven, CT

2The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH

3Neurocritical Care Society, Chicago, IL

4Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Department of Critical Care Nursing, Kano, Nigeria

5Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Department of Neurosurgery, Kano, Nigeria

6Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Department of Anesthesia, Kano, Nigeria

7University of Washington, Department of Neurology, Seattle, WA

8Rush University College of Nursing, Chicago, IL

9Kuwait University, Faculty of Medicine, Health Sciences Center, Kuwait City, Kuwait