Tricks of the Trade: A Stepwise Approach to Managing Post-TBI Agitation

Published on: November 08, 2024

Introduction

Patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) commonly develop agitation during their recovery. Post-TBI agitation (PTA) can be caused by localized injury to the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, cingulate gyrus, or amygdala [1,2], or it could also result from a more widespread injury (e.g., diffuse axonal injury [DAI]). PTA has been linked to impairments in memory, attention, and emotional regulation, with potential symptoms including aggression, restlessness, disinhibition, and emotional lability [1]. This behavioral complication of TBI may create safety issues for patients and staff while interrupting care. In severe cases, it can lengthen hospitalization and impact functional recovery [2].

PTA can occur immediately after an injury, after the return of consciousness, or in a delayed fashion. Symptoms may be transient or long lasting and can exacerbate preexisting psychiatric conditions [2,3]. PTA may also occur in isolation or in conjunction with other symptoms associated with delirium, such as deficits in attention and awareness [4]. Further, it is important to recognize that agitation in patients with TBI may have a treatable underlying cause such as pain, discomfort, or anxiety. For these reasons, the evaluation and management of PTA is nuanced and requires thoughtful consideration. Nurses that care for TBI patients should receive focused education on PTA as they spend the most time with patients, are responsible for reporting their assessments, and exercise discretion when administering as needed medications. Frontline team members such as advanced practice providers may initially respond to patient concerns, and should be prepared to evaluate and manage PTA.

Although most literature on PTA originates from the rehabilitation setting, some insights may be translatable to the acute phase of care. PTA can be challenging for hospital clinicians to manage without clear guidance, and the following stepwise approach may help guide evaluation and management of PTA in the acute care setting.

Step 1: Assess agitation

There are several tools that can be used to assess PTA. However, as TBI patients can exhibit many different cognitive symptoms, it is important to distinguish PTA from other syndromes. For example, patients with PTA may exhibit additional signs of delirium, which should be assessed using a validated tool [4,5]. The Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) is perhaps the most widely used tool to assess for delirium in the ICU [6], though it may have some limitations in patients with severe neurological injury. A recently developed tool called the Fluctuating Mental Status Examination (FMSE) may be a more reliable way to identify delirium in neurocritically ill patients, especially those with aphasia or other severe neurologic deficits [7]. On the other hand, some TBI patients may also develop signs of agitation as part of paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity (PSH), an entity which is distinct from delirium and PTA and which is typically associated with more pronounced autonomic symptoms [1].

Once other syndromes have been considered, agitation should be assessed and monitored using a validated scale. For example, the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) is often used and documented by bedside ICU nurses [8]. While it is not specifically for TBI patients, it can be used with intubated and non-intubated patients alike irrespective of their neurological deficits, and can be repeated multiple times in a shift to monitor for changes. Meanwhile, the Agitated Behavior Scale (ABS) is a tool that was developed to assess agitation in the acute and subacute period after TBI [9], with assessments often completed once per day and scores monitored by the treatment team to trend agitation over time or evaluate a patient’s response to various interventions. The Rancho Los Amigos Scale [10] is another commonly used tool that assesses agitation while also monitoring other cognitive and behavioral symptoms throughout a patient’s post-TBI recovery.

Step 2: Address confounding conditions

As many factors can impact agitation in TBI patients, it is important to consider a range of potentially confounding conditions. This includes pain, excessive stimulation from the environment, metabolic disturbances, infection, hypoxemia, urinary retention, nausea, sleep deprivation, or constipation [1,4]. Pain should be assessed and treated prior to treating agitation. Potential neurologic complications such as mass effect, hydrocephalus, and seizures should also be assessed and treated if identified [1,4]. A thorough history should be obtained to identify any preexisting psychiatric conditions and medication regimens that may need to be reinstituted [3]. Because PTA can also mimic acute intoxication or substance withdrawal, clinicians should review toxicology reports and obtain relevant social history. Trauma patients often have a variety of overlapping conditions and risk factors that contribute to behavioral complications, so a broad differential should be considered in the diagnostic evaluation of agitation in a TBI patient.

Step 3: Implement non-pharmacologic interventions

As medications can worsen PTA, clinicians should maximize behavioral and environmental modifications to reduce PTA when able [1-3]. For example, patients with impaired memory can benefit from frequent reorientation and being surrounded by familiar objects and people. Staff should speak slowly, allow time for responses, and focus on one topic at a time [1,5]. Patients with attention and concentration deficits can benefit from less stimulation (e.g., noise, light, touch), limited distractions, and frequent breaks to rest [1]. It is also important to ensure that eyeglasses and/or hearing aids are easily accessible to patients who use them.

Impulsive patients may benefit from verbal and written reminders. Restraints should be avoided whenever possible to reduce anxiety and fear, which may exacerbate distress and agitation. Mittens may be a better-tolerated alternative when patients are likely to pull on important lines, drains, or tubes [1,5]. Sleep quality should be assessed daily to ensure patients are getting adequate rest at night. Initiating a nighttime routine, darkening the room, reducing noise, clustering care, and avoiding unnecessary interruptions at night can improve sleep [4]. Mobility in the ICU is important and can help to reduce delirium [5]. While many of these recommendations are sensible, they may be easy to overlook when working in a busy clinical environment. Bedside nurses are especially well-positioned to optimize non-pharmacologic interventions to reduce PTA and should be involved in multidisciplinary discussions.

Step 4: Review and reduce offending medications

Many medications that are commonly used to care for TBI patients can worsen agitation. It is important to review all ordered medications and reduce or discontinue agents with unfavorable side effect profiles. It is also important to make medication changes in a stepwise fashion, so that responses can be adequately assessed.

For example, levetiracetam is a commonly prescribed antiseizure medication that may worsen agitation in some patients [11]. Switching to another antiseizure medication under the guidance of a neurologist may therefore be helpful in addressing agitation. Similarly, benzodiazepines may worsen agitation, are a known risk factor for delirium, and are associated with worse outcomes in TBI patients [3, 4]. As a result, this class of medications should ideally be avoided when treating PTA. However, high doses of benzodiazepines may be needed to control seizures or elevated intracranial pressure in some cases. In these circumstances, benzodiazepines should eventually be weaned when it is deemed safe to do so, albeit in a gradual way to prevent withdrawal. On the opposite end of the spectrum, neurostimulants such as methylphenidate and amantadine may improve PTA in some cases or make it worse in others [1-3]. If neurostimulants do worsen PTA, they should be discontinued.

Step 5: Pharmacologic management of PTA

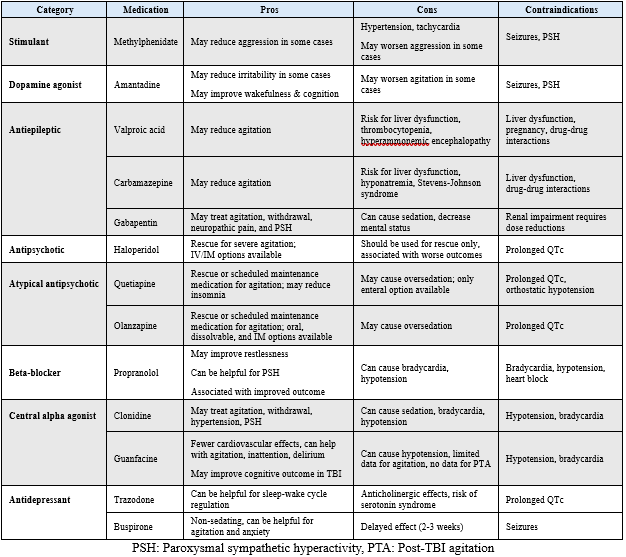

If previous steps are insufficient in managing PTA, medications may be needed to ensure patient and staff safety. It is important to highlight that there are limited data to guide pharmacologic management of PTA [1-3], and more research is needed to evaluate outcomes when using various classes of medications. In the meantime, clinicians are left to extrapolate data and tailor regimens based on individual characteristics and responses to therapy. For moderate-to-severe PTA, there are several categories of medications to choose from, each with varying mechanisms [1-3,12] (Table 1). Consultation with a pharmacist is recommended when prescribing medications for PTA as there are many caveats regarding dosage, monitoring, and drug-drug interactions.

Table 1: Pharmacologic agents used to manage post-TBI agitation

Summary

Agitation is a common behavioral complication of TBI, and thoughtful assessment is required to distinguish PTA from other related syndromes. Nurses and other healthcare workers that care for TBI patients should receive education on PTA. Validated tools should be used to assess agitation and monitor response to therapies. It is important to evaluate and treat confounding conditions such as pain, and behavioral and environmental interventions should be optimized before starting medications to treat agitation. In parallel, other medications that can worsen agitation should be reduced or discontinued. For ongoing moderate-to-severe PTA, several categories of medications are available with varying mechanisms, and consultation with a pharmacist is highly recommended. Although there are limited data to guide practice, a stepwise approach may help guide evaluation and management of PTA. However, patient responses to interventions may vary, so patients should be closely monitored. More research is needed to better understand PTA in the acute care setting.

References

- Capizzi A, Woo J, Verduzco-Gutierrez M. Traumatic Brain Injury: An Overview of Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Medical Management. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Mar;104(2):213-238. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.11.001. PMID: 32035565.

- Rahmani E, Lemelle TM, Samarbafzadeh E, Kablinger AS. Pharmacological Treatment of Agitation and/or Aggression in Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review of Reviews. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2021 Jul-Aug 01;36(4):E262-E283. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000656. PMID: 33656478.

- Robert S. Traumatic brain injury and mood disorders. Ment Health Clin. 2020 Nov 5;10(6):335-345. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2020.11.335. PMID: 33224691; PMCID: PMC7653730.

- Roberson SW, Patel MB, Dabrowski W, Ely EW, Pakulski C, Kotfis K. Challenges of Delirium Management in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Practice. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2021;19(9):1519-1544. doi: 10.2174/1570159X19666210119153839. PMID: 33463474; PMCID: PMC8762177.

- Reznik ME, Slooter AJC. Delirium Management in the ICU. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019 Nov 14;21(11):59. doi: 10.1007/s11940-019-0599-5. PMID: 31724092.

- Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Speroff T, Gautam S, Margolin R, Hart RP, Dittus R. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001 Dec 5;286(21):2703-10. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703. PMID: 11730446.

- Reznik ME, Margolis SA, Moody S, Drake J, Tremont G, Furie KL, Mayer SA, Ely EW, Jones RN. A Pilot Study of the Fluctuating Mental Status Evaluation: A Novel Delirium Screening Tool for Neurocritical Care Patients. Neurocrit Care. 2023 Apr;38(2):388-394. doi: 10.1007/s12028-022-01612-1. Epub 2022 Oct 14. PMID: 36241773; PMCID: PMC10101875.

- Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O'Neal PV, Keane KA, Tesoro EP, Elswick RK. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Nov 15;166(10):1338-44. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. PMID: 12421743.

- Wilson HJ, Dasgupta K, Michael K. Implementation of the Agitated Behavior Scale in the Electronic Health Record. Rehabil Nurs. 2018 Jan/Feb;43(1):21-25. doi: 10.1002/rnj.297. PMID: 27775164.

- Lin K, Wroten M. Ranchos Los Amigos. [Updated 2022 Aug 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448151/

- Strein M, Holton-Burke JP, Stilianoudakis S, Moses C, Almohaish S, Brophy GM. Levetiracetam-associated behavioral adverse events in neurocritical care patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2023 Feb;43(2):122-128. doi: 10.1002/phar.2760. Epub 2023 Jan 16. PMID: 36606737.

- Jiang S, Hernandez M, Burke H, Spurling B, Czuma R, Varghese R, Cohen A, Hartney K, Sullivan G, Kozel FA, Maldonado JR. A Retrospective Analysis of Guanfacine for the Pharmacological Management of Delirium. Cureus. 2023 Jan 5;15(1):e33393. doi: 10.7759/cureus.33393. PMID: 36751225; PMCID: PMC9899070.

Author Affiliations

-

Neurocritical Care Nurse Practitioner

Advanced Practice Supervisor

Department of Neurological Surgery

UC Davis Medical Center