Pride in Neurocritical Care: Sexual and Gender Minorities and Neurocritical Care Health Professionals

Published on: July 06, 2021

As part of broader diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts within NCS, the Sexual and Gender Minority (SGM) subcommittee of the Inclusion in Neurocritical Care Committee (INCC) aspires to raise awareness about and mitigate health disparities in SGM individuals, support development of culturally sensitive neurocritical care, and promote the recruitment and retention of SGM individuals who are historically under-represented in neurocritical care and in medicine more broadly.

Sexual and gender minority people include not only many patients treated by NCS members, but many NCS members themselves. As in other minority communities, understanding health and health disparities among SGM people is critical for health care professionals to deliver the best possible care to patients. Furthermore, an appreciation for SGM health issues is crucial to fostering an environment of inclusion in our profession—an environment which will bolster the diversity of our society, attract the most talented future neurocritical care health professionals, and ensure that the composition of our society more closely resembles the populations we treat.

The history of SGM health is beyond the scope of this article, but we hope that a survey of terminology, disparities, and best practices related to SGM health will be of interest to our colleagues. Critically, identity is personal and diverse, and we do not intend to speak to the experience of all SGM individuals, but instead hope to offer information, guidance, and a call to action.

Terminology

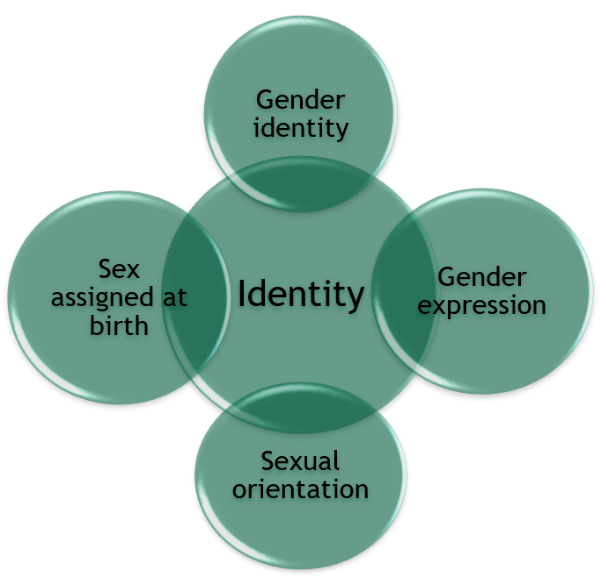

Identity is complex and multifaceted, and individuals describe their identities in different ways (Figure 1). We present common SGM terminology below (Table 1). This list is hardly exhaustive, and more expansive glossaries are easily found online.1 Such terminology is also dynamic and changes with time. For example, terms like “homosexual” or “male-to-female” have fallen out of use and may be viewed as “overly clinical,” antiquated, or pejorative.2

Figure 1. Personal identity represents a complex intersection of gender identity, gender expression, sexual orientation, and sex assigned at birth. Figure courtesy of Nicole Rosendale, MD.

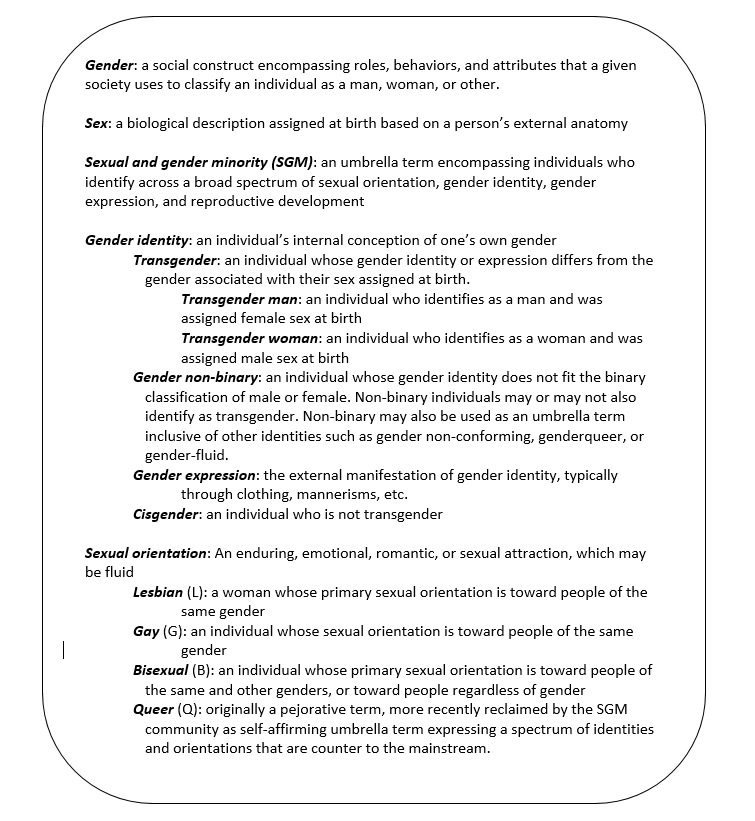

Table 1. Common terminology used to describe SGM identity.

Disparities

SGM individuals are subject to understudied health disparities across their lifespans, including higher all-cause mortality.3 SGM youth are more likely to attempt suicide. SGM adults have higher rates of certain types of cancer, higher rates of smoking and substance abuse, are less likely to have health insurance, and are more likely to be victims of hate crimes. SGM elderly experience higher rates of poverty and may have less access to partner benefits.4 More research is urgently needed to better understand SGM health inequities in neurocritical care specifically, and use of exogenous hormones, higher rates of smoking, substance abuse, HIV, depression, anxiety, and poorer access and utilization of care all likely modulate the risks of neurologic disease.5

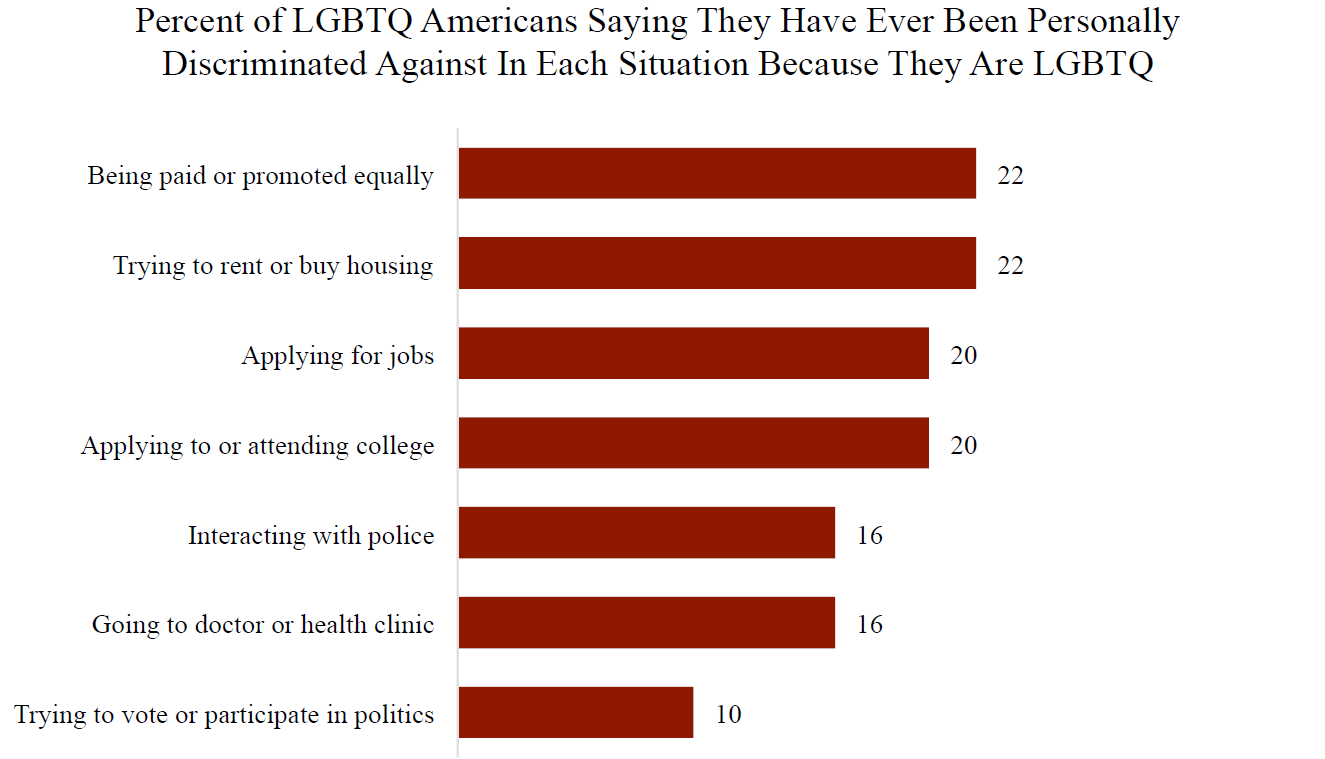

One in every six SGM individuals reports experiencing discrimination when accessing medical care (Figure 2).6 In a 2009 survey of SGM individuals, 56% of LGB and 70% of transgender respondents cited at least one instance in which they experienced discrimination in a health care setting.7 Examples of discrimination cited include being refused needed care, having health care professionals refuse to touch them, use of abusive or harsh language, being blamed for their health status, or physical roughness or abuse.

Figure 2. Survey results of 489 US adults identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer.6 Note that 16% report discrimination based on their SGM status when seeking health care.

Best Practices

SGM individuals represent a community whose very identity has historically been considered pathologic by the medical establishment. For this reason, it is all the more important that health professionals actively cultivate an inclusive environment in which to engage patients, families, and colleagues. Furthermore, better understanding our patients allows health professionals to more appropriately screen, form differentials, and counsel.

Even simple efforts can be meaningfully consequential. The use of gender-neutral and non-heteronormative language (e.g. asking about a patient or colleague’s “partner” rather than “husband” or “wife”) immediately creates a more inclusive interaction. Similarly, proactively asking about an individual’s preferred name or pronouns rather than assuming their pronouns avoids misgendering an individual (using the pronoun of the gender with which they do not identify).

While individual efforts are important, systems-level interventions are essential to ensure equitable care for SGM people. Intake forms, materials in clinical spaces (posters, brochures, etc.), the presence of gender-neutral restrooms, and hospital nondiscrimination policies all influence the inclusivity of the patient care environment.8 Transgender individuals face unique challenges in inpatient care; as primarily inpatient health professionals, we should ensure that conversations about gender identity are private, and recognize the additional stress that transgender inpatients may experience due to use of inaccurate pronouns, description by sex instead of gender, and replacement of personal clothing and other means of gender expression.8

Health professionals would benefit from further education in SGM health disparities during and after their training. A survey of American Academy of Neurology members found that about half believed sexual orientation and gender identity to be social determinants of health, and less than half felt SGM status had any bearing on neurologic illness.9

The dearth of understanding and training about SGM health reflects to some extent a dearth of SGM health-focused research. Research data specific to SGM people are limited, and most research is based on smaller observational studies and case series.10 Future research efforts should collect data about sexual orientation and gender identity in order to identify and understand SGM health disparities, and the most appropriate way to frame such data collection is well-described.2,11

Sexual and gender minorities face unique health disparities driven by complex social determinants of health. As a historically stigmatized group, SGM people face ongoing individual and systemic discrimination that perpetuates these inequities. As health professionals, we are uniquely positioned to study and mitigate health disparities, and to use our roles as community leaders to create inclusive environments for SGM and other minorities. Ultimately, we can only achieve our goal to deliver the best care of our patients when we continually advocate for inclusion in neurocritical care of all individuals—when we embrace the full diversity of our patients, our colleagues, and ourselves.

References

- Human Rights Campaign. Glossary of terms. https://www.hrc.org/resources/glossary-of-terms

- Suen LW, Lunn MR, Katuzny K, et al. What sexual and gender minority people want researchers to know about sexual orientation and gender identity questions. Arch Sexual Behav 2020;49:2301-18.

- Cochran SD, Bjorkenstam C, and Mays VM. Sexual orientation and all-cause mortality among US adults aged 18 to 59 years, 2001-2011. Am J Public Health 2016;106:918-20.

- US Department of Health and Humans Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health

- Rosendale N, Josephson SA. The importance of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health in neurology. What’s in a name? JAMA Neurol 2015;72(8):855-6.

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, National Public Radio. Discrimination in America: Experiences and views of LGBTQ Americans. 2017. https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/surveys_and_polls/2017/rwjf441734

- Lambda Legal. When Health Care Isn’t Caring: Lambda Legal’s Survey of Discrimination Against LGBT People and People with HIV. New York, NY: Lambda Legal; 2010.

- Lambda Legal, Human Rights Campaign, Hogan Lovells, New York City Bar Association. Creating equal access to quality health care for transgender patients: transgender-affirming hospital policies. 2016. https://www.lambdalegal.org/sites/default/files/publications/downloads/hospital-policies-2016_5-26-16.pdf

- Rosendale N, Ostendorf T, Evans DA, et al. American Academy of Neurology members’ preparedness to treat sexual and gender minorities. Neurology 2019;93:159-66.

- Rosendale N, Wong JO, Flatt JD, and Evans W. Sexual and gender minority health in neurology: a scoping review. JAMA Neurol 2021;78:747-54.

- Human Rights Campaign. LGBTQ-Inclusive data collection: a lifesaving imperative. 2019. https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/HRC-LGBTQ-DataCollection-Report.pdf